Touchless faucets are already a power managed device. In high traffic commercial restrooms, power strategy becomes a design decision with real consequences: uptime, maintenance workload, commissioning time, and the user experience at the sink.

Energy harvesting takes power strategy a step further. Instead of treating batteries or an AC adapter as the only options, energy harvesting systems capture small amounts of energy from the environment and store it locally to run the faucet.

In practice, most “self powered” sensor faucets harvest energy from flowing water, but there are also credible alternative strategies, including light powered (PV) designs, supercapacitor first architectures, and distributed low voltage building power approaches.

This article explains the main harvesting methods, what they change in real buildings, and what AEC teams should ask for in submittals so “battery free” does not turn into “service call heavy.”

Why energy harvesting matters in commercial restrooms

Energy harvesting is not just a green add on. In commercial restrooms, it is mainly about reducing routine maintenance and failure points.

When a building has 50, 200, or 800 sensor fixtures, battery replacement becomes an operational project. Miss the schedule and you get dead fixtures. Push the schedule too aggressively and you waste labor and materials.

Energy harvesting can help in these specific ways:

- Reduces or eliminates routine battery replacement cycles

- Cuts the risk of low voltage “brownout” behavior that causes intermittent triggering or sluggish valve response

- Improves uptime in distributed installations where electrical rough in is expensive or impossible

- Supports standardization across a large portfolio of restrooms with different fixture counts and usage rates

That said, energy harvesting is not “free power.” It is a different engineering trade.

The power budget of a sensor faucet, simplified

A touchless faucet’s energy demand comes in two patterns:

- Continuous low draw

- Sensor standby and periodic sampling

- Microcontroller and signal processing

- Sometimes an indicator LED

- Short high draw pulses

- Solenoid valve actuation (open and close)

- Any mixing valve motorization or accessory electronics

Harvesting sources are usually small and intermittent. The real enabler is the storage and power conditioning. The key question is how the faucet stores energy and delivers a reliable high current pulse to the valve without causing control resets or unstable sensor behavior.

Hydropower harvesting: turbines inside the supply path

How it works

Hydropower sensor faucets capture energy from the water that already flows through the faucet system. A small turbine or generator is placed in the supply path (often in a control box or inline module). When the faucet runs, the flowing water spins the turbine, generating electricity that charges a storage element. That stored energy then powers the sensor and valve.

Where this performs well

Hydropower harvesting aligns with commercial restroom behavior because usage is frequent. In places like schools, airports, stadiums, and hospitals, repeated activations continually recharge the storage system.

It is also attractive when:

- Running an AC adapter to every lav is costly

- Battery maintenance across many fixtures is a recurring pain

- The owner wants a long service interval without sacrificing responsiveness

What AEC teams should watch

- Minimum hydraulic conditions: the generator needs sufficient flow and pressure characteristics.

- Pressure drop: any turbine adds some resistance and may matter in borderline pressure conditions.

- Debris tolerance: strainers and filters become more important to protect turbine modules.

- Storage health: clarify how performance degrades and what “end of life” looks like.

Practical spec language ideas

- Describe the harvesting method (turbine or equivalent) and the storage method (capacitor or equivalent)

- State whether there is any backup power source and how it is used

- Provide expected operation profile under low use conditions

- Provide service access requirements for the generator module

Light powered harvesting: photovoltaic and indoor light strategies

The concept

Some sensor faucets and similar sensor fixtures use photovoltaic elements to harvest light energy. In a restroom, that generally means indoor light rather than direct sunlight. The harvested energy charges storage and powers the faucet electronics.

Benefits

- No dependency on water run time for charging

- Potentially stable energy input in 24/7 lit facilities

- No AC adapter at the sink and reduced battery burden

Constraints to understand up front

- Lighting variability: occupancy sensors and dimming can reduce charging time.

- Mounting and shading: PV needs exposure and can be blocked by partitions or design elements.

- Dust and cleaning: film buildup reduces PV performance over time.

PV works best when lighting patterns are predictable and the PV surface is serviceable. Aggressive energy saving lighting controls can make PV less predictable unless the fixture is designed for it.

Kinetic and piezoelectric harvesting: more common in dispensers, less in faucets

Kinetic harvesting is more common in devices with direct mechanical input. For touchless faucets, there is no direct user applied action, so kinetic harvesting is less straightforward.

However, plausible sources in a restroom environment include:

- Vibration and mechanical movement of connected assemblies

- Valve induced pressure pulses

- Maintenance actions that can “charge” the system

If a manufacturer claims “kinetic powered” for a touchless faucet, request clear documentation of the energy source, storage design, and expected performance in low use environments.

Supercapacitors and capacitor first architectures

Energy harvesting becomes practical when the fixture has a storage method that can accept frequent small charges and deliver short high current pulses.

Why supercapacitors are attractive

- High power delivery, good for solenoid pulses

- Very high cycle life compared with many battery chemistries

- Fast charging and tolerance for frequent charge cycles

What to clarify in submittals

- Storage element type and expected service life

- How performance changes over time

- Whether settings and calibration persist if stored energy falls to zero

- Whether the system includes a small backup battery for long idle periods, and how that backup is maintained

Supercapacitor based designs can be excellent for high traffic buildings. The risk is assuming “no batteries” means “no maintenance,” and then ignoring storage health and service access.

Alternative building power approaches that compete with harvesting

Energy harvesting is not the only way to reduce battery burden. Sometimes the best answer is to provide a cleaner building power strategy.

A) Shared low voltage power supplies (distributed DC)

Instead of an adapter at each sink, some projects use shared low voltage supplies feeding multiple fixtures. This reduces individual power bricks and can simplify maintenance.

Tradeoffs:

- A single failure can impact multiple fixtures

- Requires careful coordination for access and labeling

- Cable length and voltage drop become design variables

B) Hybrid strategies

Hybrid usually means harvesting plus a small battery backup, AC primary plus battery backup, or battery primary plus optional AC adapter. Hybrid is often the most practical approach in facilities that care about uptime.

Choosing the right approach: a comparison table for AEC teams

| Power approach | Best fit | Main advantage | Main risk to manage | What to request in submittals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water turbine harvesting + capacitor | High traffic restrooms | Reduces battery maintenance, self sustaining in busy areas | Performance under low use, debris tolerance | Storage type, low use behavior, strainer requirements, service access |

| PV harvesting + storage | Consistently lit facilities | Independent of water use cycles | Lighting controls, shading, dust | Indoor light assumptions, mounting exposure, storage details |

| Battery only | Retrofit, small installs | Simple, low coordination | Labor burden and brownout behavior | Replacement schedule, access, battery type standardization |

| AC adapter / hardwired low voltage | New builds and large projects | Stable performance and predictable O and M | Rough in coordination, transformer access | Power plan, access locations, cable length limits |

| Hybrid (AC + battery or harvest + battery) | Mission critical or premium restrooms | Uptime plus resilience | Hidden failures if backup masks primary power issues | Mode indication, failover behavior, maintenance guidance |

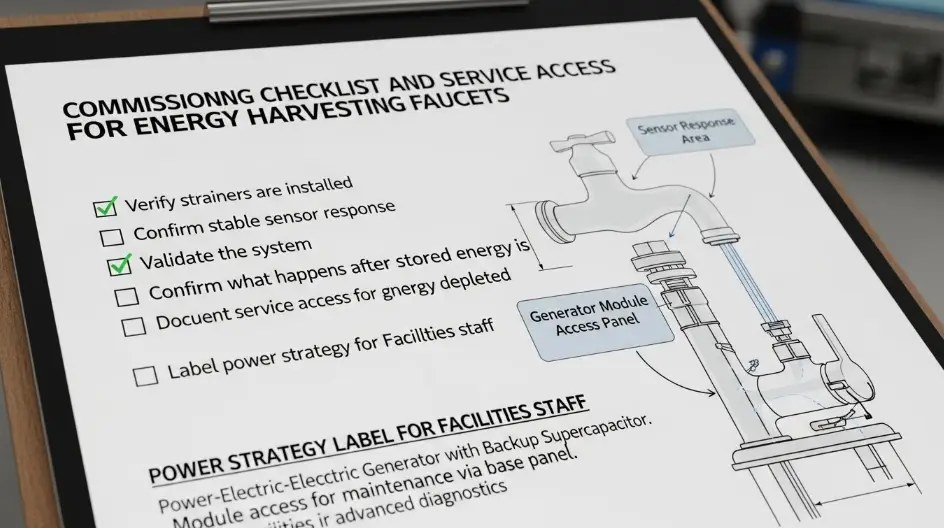

Commissioning checklist for energy harvesting faucets

Energy harvesting changes what “commissioning complete” should mean. A simple checklist can prevent long term issues.

- Verify strainers and debris screens are installed and clean

- Confirm stable sensor response and valve actuation at each fixture

- Validate the system after a period of non use if the space allows it

- Confirm what happens after stored energy is depleted and then restored

- Document service access for generator modules and control boxes

- Label power strategy for facilities staff: turbine, PV, hybrid, or battery

Practical guidance for specifications and closeout

If you want energy harvesting to reduce lifecycle cost, focus your spec language on:

- Serviceability: can the harvesting module be accessed without removing the faucet body

- Replaceable components: can the storage module be replaced if needed

- Predictable behavior under low use: what happens in a low traffic restroom or seasonal building

- Clear failure modes: does it fail safe, and how does it indicate a power problem

- Documentation: commissioning steps, troubleshooting, and maintenance schedule

Energy harvesting can be a strong fit for high traffic restrooms and portfolio scale deployments. The strongest results come when designers treat it like a system component, not a marketing checkbox.

Source links and support documents

Brand category pages (requested)

Support documents and technical references

Location: Atlanta, GA

Profile: Facility planning expert focused on large-scale commercial installations. Works with developers to implement durable, vandal-resistant soap dispensing solutions in stadiums, transit hubs, and educational campuses.